This four-day account was originally

written as a "Thank you" to all the friends and family that sponsored me on this

climb for Sound Experience. I am proud of each of

you who came through for me and for an organization that does some amazing things. It was

your support that got me through one of the greatest challenges I’ve ever faced. This four-day account was originally

written as a "Thank you" to all the friends and family that sponsored me on this

climb for Sound Experience. I am proud of each of

you who came through for me and for an organization that does some amazing things. It was

your support that got me through one of the greatest challenges I’ve ever faced.  I received more than $2,000 from 43

different donors. Ten of us generated more than $10,000 to continue life-changing

environmental programs aboard the Historic Schooner Adventuress! I received more than $2,000 from 43

different donors. Ten of us generated more than $10,000 to continue life-changing

environmental programs aboard the Historic Schooner Adventuress!

t’s been a little while now

since the climb. And what a time it’s been! The weeks and months leading up to it

were focused on training, diet and hydration. The weeks after, full of travel, fun and

decadence. Although, a bit overdue, I thought you might like to hear about the climb and

the days leading up to it.

August 4, 1998, all 12 climbers

gathered in Seattle for one last meeting. We reviewed the gear and supplies we needed to

rent. Most of the equipment was borrowed from the multitude of gear collected by Paul

& Teresa for their numerous treks to Nepal or as

R.E.I. outdoor gear testers.  The boots, crampons spiked

boot-attachments) and safety harnesses were rented to insure the most comfortable fit. We

were all a little nervous at this last meeting and hoping for some secret to make this

seemingly impossible undertaking bearable. I was expecting a pep-talk, but if anything the

last-minute cautions and reminders made it all the more real. "Don’t show up

without good sun glasses, 50 spf sun screen, lip balm, sun hat…" and it went on

and on. "And remember NO cotton up there!" The boots, crampons spiked

boot-attachments) and safety harnesses were rented to insure the most comfortable fit. We

were all a little nervous at this last meeting and hoping for some secret to make this

seemingly impossible undertaking bearable. I was expecting a pep-talk, but if anything the

last-minute cautions and reminders made it all the more real. "Don’t show up

without good sun glasses, 50 spf sun screen, lip balm, sun hat…" and it went on

and on. "And remember NO cotton up there!"

"What else is there?" I thought,

"Do I have to buy silk underwear for this thing?"

But with the help of Debbie’s roommate,

Chris, I borrowed all the

gortex, polypropylene, fleece

and wool to at least help me look like I knew what I was getting into. The truth

is, I didn’t have a clue. I knew it would be hard, but had no idea how hard. I

didn’t know that in a few short days I would be climbing up the side of a crevasse

with my ice axe at 1:00 am and by sunrise, forcing air in and out of my lungs as fast and

hard as I could. So fast, that at sea level it would have made me hyperventilate. But at

14,000 + feet, it was the only way to get the scarce oxygen where it needed to go.

we went our separate ways.  Each of us in our own

worlds—drinking as much water as we could, eating carbohydrates and attempting to

rest. I tried to concentrate on work, but all I could really do was go over my gear list

and try to relax. After work, I packed the motorcycle with all I would need for the climb

and the following two-week trip to the East Coast. During the two-hour ride to Seattle I

reviewed everything I had read and heard about the mountain and wondered if it was too

late to back out. That night at Debbie’s I packed my backpack for the last time with

an array of borrowed equipment from sun screen to a wool hat, I was ready for

anything—well, almost. Each of us in our own

worlds—drinking as much water as we could, eating carbohydrates and attempting to

rest. I tried to concentrate on work, but all I could really do was go over my gear list

and try to relax. After work, I packed the motorcycle with all I would need for the climb

and the following two-week trip to the East Coast. During the two-hour ride to Seattle I

reviewed everything I had read and heard about the mountain and wondered if it was too

late to back out. That night at Debbie’s I packed my backpack for the last time with

an array of borrowed equipment from sun screen to a wool hat, I was ready for

anything—well, almost.

morning, I met with four other climbers.  We carpooled to the mountain making stops to rent necessary gear

and buy food. Finally we arrived at Mount Rainier National Park and found our way to the

"climber’s" parking lot. We reunited with the others and all enjoyed a

high-carbohydrate "last supper" at a picnic area there. After we gorged

ourselves with spaghetti prepared by Adventuress First Mate J.C., we hiked to

glacier meadow where we spent the night. We carpooled to the mountain making stops to rent necessary gear

and buy food. Finally we arrived at Mount Rainier National Park and found our way to the

"climber’s" parking lot. We reunited with the others and all enjoyed a

high-carbohydrate "last supper" at a picnic area there. After we gorged

ourselves with spaghetti prepared by Adventuress First Mate J.C., we hiked to

glacier meadow where we spent the night.

morning we woke at 5am, donned our packs

weighing as much a 65 pounds—loaded down with climbing ropes, stoves, snow shovels,

food for four days, boots and crampons. It wasn’t a long day but it was the most

difficult. After passing through the beautiful alpine meadow, the trail rose up above the

tree line and got steep and rocky. This portion of the path was on top of a sharp ridge

only wide enough for the trail. It was formed from years of the gigantic glacier pushing

silt and rocks into a pile. As it leveled off we reached the base of the

Interglacer. We

stashed our hiking boots and water purifiers—there would be no more paths or streams

ahead. The hard plastic climbing boots were heavy, and my pack was noticeably lighter

without them attached.  Onward to the

snow… Onward to the

snow…

We broke into four rope teams to tackle the ice.

I was lucky enough to be teamed-up with the two people I knew best. Al, who is one of the Adventuress’

captains and expert mountaineer, led the team. Shannon, whom I’ve known since my days

at the Girl Scouts, was next. I brought up the rear. That first day on the ice was a real

learning experience. Al coached as we climbed. "Tomorrow when we’re up

there…" He points to the summit, "you’ll have to be able to do

whatever you need to while we’re moving! If we stop every time someone has to take a

drink, we’ll never make it."

Watching the experienced climbers I noticed how

they took gentle steps, barely making a sound. I concentrated on making each step more

efficient. With thousands of steps to come, I focussed on conserving energy with every

action I made. The distraction didn’t hurt either. Before I knew it we reached the

top of the

Interglacier. That’s when the first truly breathtaking view appeared.

Below us to all sides were gigantic glaciers with only a rocky path leading us up.

It was time to take off the crampons and make

our way across the rocks. We moved slowly making sure we were not directly over anyone.

Falling rocks would have been deadly at such a severe angle. Soon we were at the next

glacier. The ice’s sure footing seemed easy after the rocks. The teams quickly found

a rhythm again. This glacier had some small crevasses.

It was the first time I got to look closely down

inside one—the white turning to blue, darker blue then black. This was also when I

realized just how small we were on this mountain. "At least ants build the

anthill," I thought. This volcano doesn’t even know we’re here!

These giant glaciers are just clumps of ice slowly sliding down its side.

When these clumps slide off a steep cliff, they split a little and form crevasses. And

here we are with ice axes, ropes and spikes on our feet zigzagging our way around these

little splits trying to find a path up. Once in a while, the crevasses are too long to go

around so we have to cross them. I didn’t really think about that aspect when I

envisioned this trek—and I’m glad! These giant glaciers are just clumps of ice slowly sliding down its side.

When these clumps slide off a steep cliff, they split a little and form crevasses. And

here we are with ice axes, ropes and spikes on our feet zigzagging our way around these

little splits trying to find a path up. Once in a while, the crevasses are too long to go

around so we have to cross them. I didn’t really think about that aspect when I

envisioned this trek—and I’m glad!

I found a rhythm and focussed on my breathing. I

had to remind myself to look around at the spectacular view every so often.

Before long, we reached base-camp. The

experienced climbers quickly unpacked the shovels and began to level the ground for tents.

Al carved a kitchen, complete with a small dinette. Before long we had a small village of

tents. Stoves were lit and we began to melt snow for dinner and top off everyone’s

water bottles.

As we ate, Al told us how to prepare our gear

and ourselves to wakeup, pack all that we needed for the summit in the dark, and quickly

get moving. "The earlier we begin the easier it will be. Now let’s get to bed

and try to get some sleep"—fat chance.

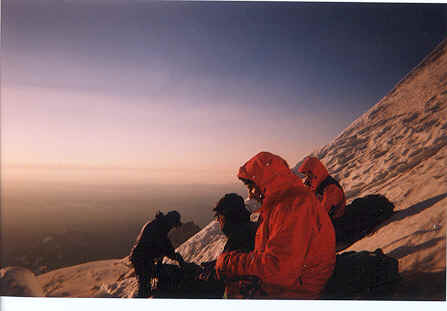

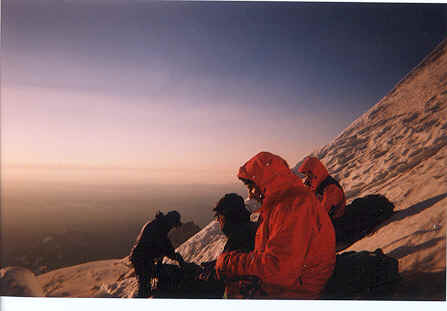

As everyone began to hunker down for the night I

perched on a distant rock sticking up out of the snow. The sun was setting and the lights

of Tacoma, Seattle, Bellevue began to twinkle and the dark outline of Puget Sound became

apparent. "There it is," I thought, "That’s why I’m up

here."

I wish I could have bottled that feeling to

share it with everyone. No words can describe it. I sat there in silence listening to the

wind pass across the glacier for a long time before returning to the tent.

I am a light sleeper to begin with. Add to that

sleeping on ice with winds gusting from random directions and the excitement of the

upcoming day… . All I could do was lie there and wait for the wake-up hail from Al.

It felt good to relax my already sore legs. The night seemed to go on forever. I tried to

figure out which tents the different snores were coming from. Finally at about 11:45 PM I

heard stirring and I thought, "This is it!"

we woke and quickly fired up stoves to melt snow. After oatmeal and a cup of hot tea, we

packed and roped up. By 1:00 am we were on our way toward the summit. Looking up into the

darkness I could see the outline of our route. A line of dots from climbers’

headlamps crisscrossed  up and out of sight. After only an

hour of climbing, as the full moon rose, we reached our first and what would be our most

technical obstacle. A large 12-foot-wide crevasse stretched across the glacier as far as I

could see. To try and find a way around it would have taken too much time. Upon seeing the

gaping hole and our little selves peering into it with our head lamps only penetrating a

few feet into its vast depths, all I could think was, "Oh well, we’ll have to

turn around. Maybe another day…" up and out of sight. After only an

hour of climbing, as the full moon rose, we reached our first and what would be our most

technical obstacle. A large 12-foot-wide crevasse stretched across the glacier as far as I

could see. To try and find a way around it would have taken too much time. Upon seeing the

gaping hole and our little selves peering into it with our head lamps only penetrating a

few feet into its vast depths, all I could think was, "Oh well, we’ll have to

turn around. Maybe another day…"

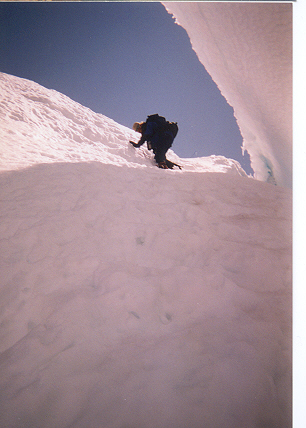

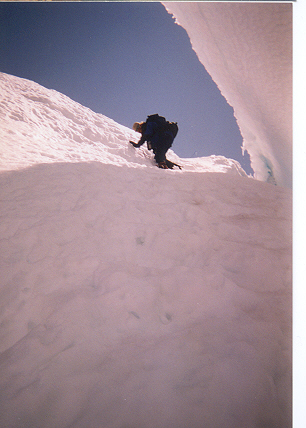

Al and the other climb leaders immediately began

to discuss and prepare for the crossing. There were remnants of a snow bridge that had

collapsed. All that remained was a large chunk of ice about six feet below. We belayed

each other down and across the ice. The  tricky

part was jumping from the chuck of ice to the wall of ice and climbing with our ice axes

up to the side where we untied and waited to help the next person. tricky

part was jumping from the chuck of ice to the wall of ice and climbing with our ice axes

up to the side where we untied and waited to help the next person.

The experienced mountaineers were having a great time

teaching the rest of us how to climb and use new belaying techniques. Once everyone was

safely across, we teamed up again. The experienced mountaineers were having a great time

teaching the rest of us how to climb and use new belaying techniques. Once everyone was

safely across, we teamed up again.

Looking up the steep trail, I wondered how many

more obstacles lay ahead. Rope leaders picked up the pace a bit to make up for lost time.

I began to realize the scope of this thing—the danger and importance of good

technique. This was the hardest part of the climb for me. My legs were heavy, my hands

cold and I began to get sloppy with my steps. I wondered if we were ever going to rest.

But even if I stopped for a moment to double up on a breath or re-position the ice axe,  I would get a tug on the rope from Al and

Shannon who were steadily forging upward. I would get a tug on the rope from Al and

Shannon who were steadily forging upward.

There wasn’t even time to

look down and enjoy the sunrise over the Cascade Mountains. I did catch a glimpse or two

but I wouldn’t call it an enjoyable view.

Between the slathering of sunscreen, dripping

sweat and constant forced, heavy breathing though my nose and mouth, I turned into some

kind of a sniveling, snarling, gooey monster. But I didn’t care. One foot in front of

the other. And when it was too steep for that, we turned to the side using what I believe

is a French climbing technique. This was slightly more difficult because you had to lift

your feet higher, but it used a new set of muscles. Quite a welcomed change for the first

few minutes.

Then it was just the same: move one foot,

breathe, move the other, breathe, move the ice axe, then start over. And it went on until

a rhythm was formed. It became a meditation game. I thought about everyone who sent

donations and supported me, all the encouraging words and all the lies I told my mom so

she wouldn’t worry. If she could see me now, she’d never sleep again! Left,

right, move the axe… Then I thought of how I was going to tell you all that I

didn’t make it. That I should have trained one more hour, one more day each

week—I had six months, I should have trained harder! Left, right, move the axe…

What do you know, now we’re at 12,600 feet only 1,810 more vertical feet to go. Left,

right, move the axe… I wonder how many more steps that is. Maybe I should have

counted how many steps it takes from the parking lot—I’ll bet no one has ever

done that! If my cousin Joe were here, he’d help me calculate it. Hell, if he were

here, I hope he’d be trying to talk me into turning around! On and on my mind

wandered.

I’ve read it in books and been told by

experienced mountaineers that climbing Rainier is a mental game—a long steep trek

that wears down the mind as well as the body with each icy step. Most of the climbers in

my group told me that they kept pushing on-never doubting that they’d make it.

I guess I work differently than that, because I fully prepared what I was going to say to

each person I might come in contact with for the next six months. I would say things like,

"Well, I’m no mountain climber… only about half of the people who attempt

the summit actually make it all the way to the top… my shoes were the wrong size and

the weather made it extraordinarily difficult." I guess preparing for the worst is

how I prevent it from getting the best of me. And it’s what got me though those times

when all I wanted to do is collapse in the snow.

As I vividly imagined telling my nephew,

J.B.,

that I didn’t have it in me, and explaining to Debbie how she was right I didn’t

train hard enough, it hit me. I could suffer though this for as long as it takes. Because

I sure as hell ain’t coming up this mountain again! There are people in this world

suffering real hardships, I am just walking up a hill—the longest, steepest

freakin’ hill I’ve ever seen, but still just walking up a hill.

By then, we were at 13,600 feet. I noticed the

rope team ahead of us stopping for our second (and final) break.

As I got closer to the rest spot, I could see

those already seated eating and drinking. The last few steps were the hardest. Finally I

arrived. I fell to my knees, drove my ice axe into the snow and fastened my pack to it. I

got out water and began to drink. The altitude made me nauseous. I knew I had to keep my

energy up, so I forced down some chocolate and nuts with big gulps of water.

Every cell in my body seemed to soak it up the

calories. As the rest of our group arrived, some climbers seemed like they were just out

for a walk. The rest of us looked like we were going to die—one step away from not

being able to continue. Some had altitude sickness so bad they couldn’t even keep the

water down. That’s when the pep talk came (not a moment too soon)! Al put it in

perspective, "There are times to turn around and times to got for it. The weather is

perfect, we are making great time, you all look strong… lets do it!"

We slowly put our packs on and began to head for

the final leg of the trip. We each seemed to move with more confidence. And I knew we were

all going to make it.

All 12 of us at the summit (I'm on the left)

Shannon, Al and Me on top of

the world.

A panoramic shot of the top of

Mount Rainer. Those dots are people crossing the volcanic crater.

|

This four-day account was originally

written as a "Thank you" to all the friends and family that sponsored me on this

climb for Sound Experience. I am proud of each of

you who came through for me and for an organization that does some amazing things. It was

your support that got me through one of the greatest challenges I’ve ever faced.

This four-day account was originally

written as a "Thank you" to all the friends and family that sponsored me on this

climb for Sound Experience. I am proud of each of

you who came through for me and for an organization that does some amazing things. It was

your support that got me through one of the greatest challenges I’ve ever faced.  I received more than $2,000 from 43

different donors. Ten of us generated more than $10,000 to continue life-changing

environmental programs aboard the Historic Schooner Adventuress!

I received more than $2,000 from 43

different donors. Ten of us generated more than $10,000 to continue life-changing

environmental programs aboard the Historic Schooner Adventuress!

The boots, crampons spiked

boot-attachments) and safety harnesses were rented to insure the most comfortable fit. We

were all a little nervous at this last meeting and hoping for some secret to make this

seemingly impossible undertaking bearable. I was expecting a pep-talk, but if anything the

last-minute cautions and reminders made it all the more real. "Don’t show up

without good sun glasses, 50 spf sun screen, lip balm, sun hat…" and it went on

and on. "And remember NO cotton up there!"

The boots, crampons spiked

boot-attachments) and safety harnesses were rented to insure the most comfortable fit. We

were all a little nervous at this last meeting and hoping for some secret to make this

seemingly impossible undertaking bearable. I was expecting a pep-talk, but if anything the

last-minute cautions and reminders made it all the more real. "Don’t show up

without good sun glasses, 50 spf sun screen, lip balm, sun hat…" and it went on

and on. "And remember NO cotton up there!"

Each of us in our own

worlds—drinking as much water as we could, eating carbohydrates and attempting to

rest. I tried to concentrate on work, but all I could really do was go over my gear list

and try to relax. After work, I packed the motorcycle with all I would need for the climb

and the following two-week trip to the East Coast. During the two-hour ride to Seattle I

reviewed everything I had read and heard about the mountain and wondered if it was too

late to back out. That night at Debbie’s I packed my backpack for the last time with

an array of borrowed equipment from sun screen to a wool hat, I was ready for

anything—well, almost.

Each of us in our own

worlds—drinking as much water as we could, eating carbohydrates and attempting to

rest. I tried to concentrate on work, but all I could really do was go over my gear list

and try to relax. After work, I packed the motorcycle with all I would need for the climb

and the following two-week trip to the East Coast. During the two-hour ride to Seattle I

reviewed everything I had read and heard about the mountain and wondered if it was too

late to back out. That night at Debbie’s I packed my backpack for the last time with

an array of borrowed equipment from sun screen to a wool hat, I was ready for

anything—well, almost.

We carpooled to the mountain making stops to rent necessary gear

and buy food. Finally we arrived at Mount Rainier National Park and found our way to the

"climber’s" parking lot. We reunited with the others and all enjoyed a

high-carbohydrate "last supper" at a picnic area there. After we gorged

ourselves with spaghetti prepared by Adventuress First Mate J.C., we hiked to

glacier meadow where we spent the night.

We carpooled to the mountain making stops to rent necessary gear

and buy food. Finally we arrived at Mount Rainier National Park and found our way to the

"climber’s" parking lot. We reunited with the others and all enjoyed a

high-carbohydrate "last supper" at a picnic area there. After we gorged

ourselves with spaghetti prepared by Adventuress First Mate J.C., we hiked to

glacier meadow where we spent the night.  Onward to the

snow…

Onward to the

snow…

These giant glaciers are just clumps of ice slowly sliding down its side.

When these clumps slide off a steep cliff, they split a little and form crevasses. And

here we are with ice axes, ropes and spikes on our feet zigzagging our way around these

little splits trying to find a path up. Once in a while, the crevasses are too long to go

around so we have to cross them. I didn’t really think about that aspect when I

envisioned this trek—and I’m glad!

These giant glaciers are just clumps of ice slowly sliding down its side.

When these clumps slide off a steep cliff, they split a little and form crevasses. And

here we are with ice axes, ropes and spikes on our feet zigzagging our way around these

little splits trying to find a path up. Once in a while, the crevasses are too long to go

around so we have to cross them. I didn’t really think about that aspect when I

envisioned this trek—and I’m glad!

up and out of sight. After only an

hour of climbing, as the full moon rose, we reached our first and what would be our most

technical obstacle. A large 12-foot-wide crevasse stretched across the glacier as far as I

could see. To try and find a way around it would have taken too much time. Upon seeing the

gaping hole and our little selves peering into it with our head lamps only penetrating a

few feet into its vast depths, all I could think was, "Oh well, we’ll have to

turn around. Maybe another day…"

up and out of sight. After only an

hour of climbing, as the full moon rose, we reached our first and what would be our most

technical obstacle. A large 12-foot-wide crevasse stretched across the glacier as far as I

could see. To try and find a way around it would have taken too much time. Upon seeing the

gaping hole and our little selves peering into it with our head lamps only penetrating a

few feet into its vast depths, all I could think was, "Oh well, we’ll have to

turn around. Maybe another day…"  tricky

part was jumping from the chuck of ice to the wall of ice and climbing with our ice axes

up to the side where we untied and waited to help the next person.

tricky

part was jumping from the chuck of ice to the wall of ice and climbing with our ice axes

up to the side where we untied and waited to help the next person.  The experienced mountaineers were having a great time

teaching the rest of us how to climb and use new belaying techniques. Once everyone was

safely across, we teamed up again.

The experienced mountaineers were having a great time

teaching the rest of us how to climb and use new belaying techniques. Once everyone was

safely across, we teamed up again.  I would get a tug on the rope from Al and

Shannon who were steadily forging upward.

I would get a tug on the rope from Al and

Shannon who were steadily forging upward.